This podcast is the end of a long journey—although it could have been longer. I mean that my work on the Irish Famine should have begun when I was a member of the Department of Modern History at University College, Dublin (UCD), in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As the visiting American historian, I could have been excused from dealing with Irish topics in the department’s fortnightly tutorial system. However, I quickly learned that without some knowledge of Irish history, I would be left out of many of the conversations in the snug at Hartigan’s Pub on Lower Leeson Street, the off-campus headquarters of UCD’s male historians. Unlike many American academics at the time, Irish historians talked about their profession.

Of course, in Ireland Irish history can easily become family history, and family history can sometimes drift into gossip, and from there it might just wander off into the bogs—a confusing mix for a visiting, clueless Yank. Nevertheless, so as not to be left completely adrift, I opted to swat up some of the set topics in Irish history normally assigned in the tutorials. Oddly enough, the Great Irish Famine was not one of them. At the time, there were only a few books available on the subject, and I recall little conversation, academic or otherwise, about that singular, cataclysmic event. I eventually realized that most of my Irish colleagues, all excellent historians, belonged to the “revisionist|” generation, dedicated to writing “professional” Irish history drained of the old nationalist emotions and biases that had collected around volatile topics like the Famine. With things heating up in Northern Ireland, there may not have been much enthusiasm to stir that particular pot.

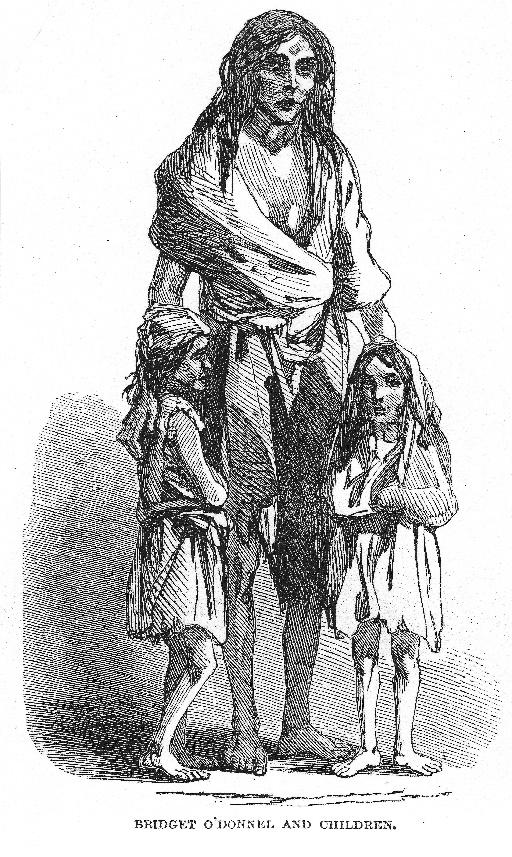

At any rate, my interest in the Irish Famine developed only gradually after I left Ireland and began teaching a survey of Irish history, first in Germany and then back in the United States. Then, in 1997, in recognition of the sesquicentennial of “Black ‘47,” I organized a series of public lectures on the Famine sponsored by the Union Institute and University where I taught in Cincinnati, Ohio. While preparing my own talk, I suggested to my wife, Leslie A. Williams, that, as an art historian, she might provide an analysis of the period engravings that had appeared in the Illustrated London News and Punch. She did, and eventually published the results. After the lectures, I had expected that we would both return to our original research interests; I to my work in Irish travel accounts, and she to her interests in Victorian genre paintings.

However, Leslie could not let go of the Famine. Or, perhaps, the Famine would not let go of her. Although we both shared a Pennsylvania–German background, unlike me, my wife had Irish ancestry. A great-great grandfather had come over in the 1840s, eventually becoming a captain in the Union army (we still have his papers and sword). Perhaps a certain outrage built up as she extended her research from illustrations to texts and from periodicals to the coverage of the Famine by the major British newspapers. A book began to emerge with the working title “Killing Remarks.” Unfortunately, before she could put the finishing touches on the manuscript she was diagnosed with cancer and died in 2001. I promised her that I would edit her work for publication. Her book, Daniel O ‘Connell, the British Press, and the Irish Famine: Killing Remarks, appeared in 2003.

With Leslie’s book published, I was now able to write up my research on Irish travelogues and early tourism. I eventually published Tourism, Landscape, and the Irish Character: British Travel Writers in Pre-Famine Ireland in 2008 and Creating Irish Tourism: The First Century, 1750–1850 in 2010. Both books touched on Famine-related topics, and now found that I could not let go of the subject. Although I knew enough about the event to be impressed by its complexity, I still lacked a clear sense of how all the pieces—geography and ecology, land ownership and land use, potato monoculture, demographic factors, British attitudes toward the Irish, as well as religious, political and economic issues—fitted together. My reading in systems theory encouraged me to try to understand the systemic relations that link all these elements.

In writing my book, Ireland’s Great Famine, Britain’s Great Failure, and then in developing this podcase, I have drawn upon my extensive reading in Irish travel accounts written before, during and just after the Famine. In addition, I have also extended my wife’s research on the British press with my own investigations of newspaper, periodical and other contemporary accounts. Fortunately, since the mid-1990s, there has been a considerable increase in the amount of scholarship dedicated to the Famine, most of it produced by Irish historians. While I have not been able to read everything that has been published, I am a grateful beneficiary of much of this recent work.

Thank you for reading this, and I hope that you enjoy the podcast. Bill Williams